Everyone experiences anxiety at times – and that’s a good thing. Get too close to the edge of a cliff and you should feel anxious. After all, you’re in danger of falling and doing harm to yourself. God has given us these warning signals to protect us. We can’t escape them, and we shouldn’t want to … Except when our anxiety isn’t actually protecting us. Let me explain.

Anxiety is God’s Gift for Self-Protection

Note first that technically a distinction can be made between anxiety and fear, but for this little article, please bear with me conflating the two.

We are made by God to have a sense of self-protection. Even crawling babies will avoid moving onto a glass surface if they see a drop off beneath. This is the beginning of the anxiety we experience near cliffs. We could go on with examples: smelling smoke in the house, spying a snake in our path, seeing a car coming toward us on the wrong side of the road. We also learn to protect ourselves psychologically: A simple example is from my ancient dating days. I would be afraid to ask out a girl I liked for fear she would say “no” and then I would suffer psychological harm by feeling rejected. But avoiding psychological “danger” sometimes carries a risk on the opposite side: I am in danger of missing out on a relationship if I duck the risk of asking her out. I wouldn’t have found love if I’d avoided the “danger” of asking my wife out the first time.

God has made us with anxious reactions to protect us: we ascertain danger or uncertainty ahead, and our body reacts to prepare us for the danger: primarily either to face it head on (“fight”) or to escape it (“flight”).

Misjudging the Danger

But what if our bodies and minds misjudge the danger? We can underestimate dangers (like teens who take risks too freely), but more commonly we overestimate them. There are two ways we do this: seeing a threat when there is none or overestimating a threat that is real.

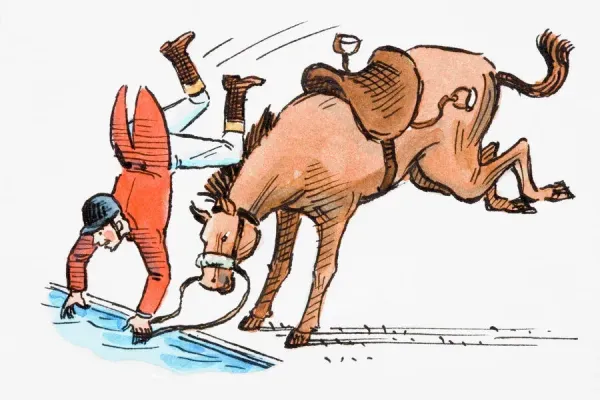

The fear response is fine-tuned over time by our experiences and our reactions to them. Recall the old adage that if you fall off a horse you should get right back on it? We all have unpleasant events we don’t want to repeat, but there is a degree of danger in everything we do. If you are an avid equestrian, then you accept the danger of riding the horse again for the benefit of the joy of riding. If you don’t get back on the horse right away but avoid it because you are afraid of falling, you are “rewarding” your fear by affirming it and the longer you wait to try again, the harder it will be. Avoiding reasonable risks over time makes anxiety stronger as you train your anxiety response to be increasingly sensitive to the thing avoided.

Humans are made in God’s image and have skills other animals lack (except maybe in very primitive forms). Key among these is the ability to reflect on the past and to anticipate the future. These are wonderful gifts from God, too. But in our fallen state, we can misjudge things. We can overstate the harm done in the past or the risk of something happening in the future, leading again to avoidance of things that might not be as dangerous as we think them to be. Worry, for example, is simply trying to anticipate what will happen in the future and formulate your response to decrease anxiety in the present. You read that right: worry creates anxiety now and trying to develop a greater sense of certainty for the future reduces the anxiety you are having now regarding what will happen later. Worry is often unfruitful because there are so many futures we can imagine and so we cannot have a plan for dealing with every one of them. Once you insist on quelling anxiety by having such a plan, you jump on the hamster wheel of anxiety.

To summarize, anxiety can be healthy and helpful, but it can also overestimate dangers or anticipate future dangers that most likely will never come to be. Our “flight” response is often to avoid things that cause us anxiety, further strengthening the anxiety. Add to this our thoughts of God in the process. Christians are often more frustrated with anxiety because they realize in some ways it is saying, “I’m not so sure God will take care of me, so I better figure this out myself.” There is a balance here: I depend on God to be safe in the car, but I put on my seatbelt and don’t drive when I’m really sleepy.

Our goal is to take reasonable precautions, but not to compromise doing what we are called to do by avoiding all anxiety – particularly anxiety that is excessive and in response to highly unlikely potential dangers.

What to do

Here are a few basic suggestions to managing unhelpful anxiety.

1. Reset your thinking about anxiety. We often think any time we feel anxious we need to act, assuming we actually are facing a danger of some sort. As we have seen, this can be true, but at other times it is exaggerated with respect to the actual danger, or in response to a potential, hypothetical danger in the future. We need to consider whether feeling anxious is due to a real danger or not. One of my favorite phrases is important here: Just because you feel afraid doesn't mean you’re in danger. Think of watching a movie. You can feel afraid as Tom Cruise hangs by one hand off a building, but you’re sitting comfortably, munching popcorn. The fun of the movies is to feel emotion while knowing it isn’t real. Don’t assume anxiety means danger. Pause to think about the actual situation, not just how you are feeling. Anxiety is God’s gift, but we easily distort its purpose.

2. Once you have the above mindset, ask yourself: “Is the danger imminent and actionable?” “I smell smoke in the kitchen” is both of these. “What if I get lost in the woods some day?” is neither. If action can be taken right now to reduce a real danger, do it! Investigate the smell of smoke. But if not, remind yourself that the anxiety you feel isn’t the helpful kind and requires no action. It will dissipate in a while.

3. That means you may need to feel anxious and take no action to stop it. This is challenging, but vitally important. When false anxiety is present and you react, you can strengthen your anxiety. Rather, notice it and say, “Oh, here’s my overanxious mind stirring things up.” Accept that you may feel uncomfortable but realize that in doing so you’re training your anxiety. As in strengthening muscles, no pain, no gain.

4. In considering these things, bear in mind not just what you might avoid, but what you are moving toward. As Christians, we move toward obedience to God – even when it is anxiety-evoking. Sharing the Gospel or going to the mission field might be scary, but they may be your calling. More simply, striking up a conversation with the new person at church might evoke anxiety, but it is not danger, and you do want to show the love of Christ.

In the end, we want to follow Christ and do what is right, even if it makes us feel uncomfortable. Feelings are not “truths” about what is. They are good things that can be overdone (just as food is good, but too much of it isn’t). Ask more of what God would have you to do than how can you escape this feeling or avoid having it in the first place.

God has given us breath for today, and he calls us to seek his glory in it rather than spend it trying to avoid good things that might be important, even if they make us feel uncomfortable. Better to follow Christ and experience some anxiety than to avoid anxiety only to fail in our calling.